It is widely accepted that the intention of Polynesian tattoo, specifically Marquesan and to some degree Samoan and Hawaiian, was purely for protection. Protection from malevolent intent, protection from the gods, from the negating effects of those of lesser status, and from the contagious sacredness (tapu/kapu) intrinsically enmeshed in mortal existence. Tattoo was regarded as a two-dimensional representation of an armor-like shell, that when populated with motifs unique to an individual, and fortified by the tehuna, or tattoo artist, who channeled the mana (power) of the gods while applying the tattoo, provided the wearer with a body shield of divine origins.

Like I said, this is a widely accepted truth, one backed by a litany of illustrative, pictorial and written documentation. I have never questioned this, for the simple fact that it makes sense.

That being said, I have also felt, for some time now, that there was a vital piece missing to this widely accepted truth. It was when I began to assess the visual content of some Marquesan tattoo art that I began to come up with a possible explanation. Sometimes things are so glaringly obvious that they are impossible to see.

First, we need to look at the definition of the word: armor.

Merriam-Webster defines it as:

Armor, n.

1: defensive covering for the body; especially : covering (as of metal) used in combat

2: a quality or circumstance that affords protection <the armor of prosperity>

3: a protective outer layer (as of a ship, a plant or animal, or a cable)

I don’t know why, but for whatever reason I have always regarded the comparison of Polynesian tattoo to armor, in the figurative sense, definitions 2 or 3, more so than 1.

The references made by Gell, Von Den Steinen and others, never claim outright that the intent was to ‘armor’ an individual, but the usage of the word is carefully applied.

There can be no mistaking the geometric nature of Polynesian tattoo; triangles, circles, squares are ubiquitous. Paka (sections) of tattoo take on rhomboid shapes while the overall appearance of a completed, body tattoo fit together like pieces of a puzzle. This is characteristic of Marquesan tattoo, but as I mentioned above, echoes of this geometric symmetry/asymmetry can be found in other genres of Polynesian tattoo as well.

When I was young I was somewhat of a nerd. Addicted to role-playing adventure games, smitten with English fantasy writers that spun tales of soul-eating swords and legions of warriors clad in armor. None of this helped my sex life, mind you.

What I did take away from my youthful days was an unwavering appreciation for the middle ages (although I would like to point out that I have never been to a Renaissance Fair(e) nor have I ever worn a codpiece). So it is through this rosy, fantasy-based lens, that I broached the possibility that Marquesan full body tattoos could be an analog to the armor of the middle ages.

Realizing that this theory could add another dimension to what instigated the agency of Polynesian tattoo art as a whole, potentially upsetting the intricate nature of what some social anthropologists argue was the reason behind Polynesian tattoo application, I proceed with caution and with the utmost respect for those professionals.

One symbol in particular always stood out to me as something that did not belong in the catalog of Marquesan tattoo art. It just so happened that one day while I sat considering the relevance of this particular motif that I began to look at the entire body tattoo from a fresh perspective.

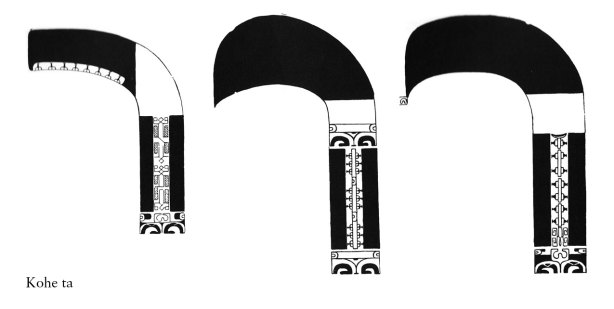

The motif in question is the kohe ta.

Before I get into explaining the meaning of the kohe ta and how it fits into my theory, I need to make a point about the evolution of Marquesan tattoo style.

There seems to be, at the least, two distinct styles of tattoo that make up the entirety of the Marquesan corpus. I disregard any of Krusenstern’s illustrations, which have always been regarded as questionable for the simple fact that they are too ‘perfect’ in the aesthetic sense–while simultaneously lacking proper detail–and do not convey the actual representation of the primitive nature of Marquesan tattoo with proper accuracy. I will state my case using the photographic and illustrative examples provided by Handy and Von Den Steinen, respectively.

These two styles seem to have been born from evolution of the art form rather than being a product of regional or stylistic differences. In other words, although each of the islands in the Marquesan group had certain specific regional characteristics in regards to the style of the tattoo that any given region produced, the distinction between the two styles that I am talking about, seem to stem from a shift in aesthetics vis-a-vis cultural evolution than from a departure from style precedence.

These two styles are referred to (by Von Den Steinen) as the ‘old’ style and the ‘new’ style. The importance of distinguishing between these two styles is that the latter is more visually and aesthetically compliant than the former, to appearing ‘armor-like’. The ‘new’ style was a pivotal shift in Marquesan tattoo and could have certainly been in response to an outside influence as it was with when the Tahitians encountered European visitors, that changed the agency of their tattoo completely ( Gell 1993, p. 123). Interestingly enough, in many of the illustrative and photographic evidence offered, there are several examples of individuals who wear a combination of both. This could reflect the fact that Marquesan tattoo, when applied to a person of higher status, began from the feet and worked upwards, over the span of many, many years, or it could have simply reflected a regional aesthetic. In those instances of individuals with this mixed style, the ‘old’ style is predominantly on the arms, and in one case on the right side of the body, with the new style on the left. This ‘new’ style is where several motifs that could be associated with elements crucial to my theory exist. The one containing the most relevance to my argument is the kohe ta.

The kohe ta is a symbol that can be found in nearly all of the photographic and illustrative examples of full body, male tattoo.

Kohe ta means sword.

Because Polynesians never mastered metallurgy or had access to raw materials (which would be the catalyst for such an event) such as iron, it is logical to deduce that an object such a sword would require introduction from an outside source. It is well documented that when Captain Cook arrived at the Hawaiian Islands, his ships were constantly being looted by the natives of anything and everything iron (Daws 1968, p.14)

Wreckage from Spanish ships prior to Cook’s contact had washed up on the shores of Kauai and the natives were able to procure several iron lashings and nails (Daws 1968, p.5), which they prized as much, or even more than, livestock.

European traders traveling the Pacific in search of a route to the Spice Islands were documented as trading small pieces of iron with the natives of various Polynesian societies in return for supplies. This practice continued up until the beginning of the twentieth century.

So it does not require an enormous amount of reason to conclude that perhaps the Marquesans were introduced to the sword in just such a way. Barter, washed up with some wreckage or acquired from a vanquished foe, the weapon could have ended up arriving in the Marquesas in any number of ways. My argument does not revolve around the introduction of the sword to Marquesan culture, but rather how it is represented in tattoo.

The kohe ta is always placed on the body in the same area: arching from the lower back onto the side of the thigh, the exact area where anyone possessing a sword would wear the weapon.

The motif is often embellished with etua (godlings), kofati (creased areas), hiku-atu (bonito tails) and mata hoata (death’s head/brilliant eyes). The pommel of the sword is more often than not, represented by a large expanse of black, and it is this portion of the tattoo that adorns the lower back. In most cases, in regard to a full body tattoo, there will be a pair of kohe ta, one on either side.

It is the placement of the kohe ta that made me look at the entire body tattoo in a different light.

As far as any early explorers or even Melville (Omoo, 1847), for that matter, has stated, there is no documentation of natives wielding swords in any way that would suggest a greater trend of utilizing a sword over a club or spear. I would even go so far as to say that even if natives had access to such a weapon, that it would not be used as intended but instead prized and kept by a chief as a trophy. It could also have been re-purposed to make other tools. To use a sword proficiently requires skill and training. It also requires sufficient care to protect it from the elements, such as saltwater and sea air. In the primitive conditions of early Marquesas, a sword would not have a long life.

This begs the question: Why would the Marquesans place such importance on something that they probably never, or only on very rare occasion, came into contact with especially to the degree of immortalizing the weapon with tattoo?

It would make sense then, that such a weapon was not only seen as a sign of prestige but also be recognized as an instrument of great power. Although this may likely be the case, I doubt that adoration for the sword alone would prompt its inclusion into the corpus of Marquesan tattoo art to the degree that would make it compulsory.

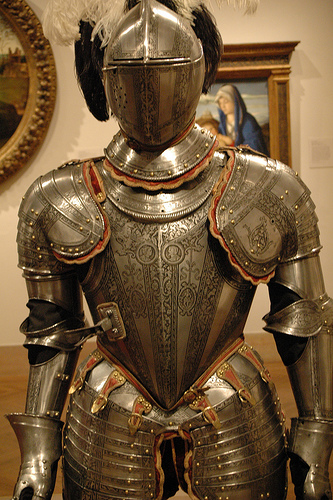

Unless of course, the sword was part of a grander vision, that when witnessed for the first time from a savage perspective, burned indelibly into the primitive psyche. This grander vision I am referring to would be the first time a Marquesan native laid eyes on a man wearing a full suit of armor.

Such an opportunity could have arisen as early as 1519-21 when Magellan, attempting to find a westward route to the Spice Islands (Moluccas, Indonesia) entered the southern Pacific after spending much time dealing with mutinies, bad weather and the loss of a ship. The account of exactly when and where he entered the Pacific is still a topic of much debate. The logbook of his expedition pilot, Francisco Albo is notoriously unreliable and other documentation of the voyage has not fared well against the test of time.

Some claim that Magellan visited Hawaii, New Zealand, and Tahiti but the only information that I could find to corroborate this claim tended to be on Christian missionary websites of which I can say, the accuracy of, is dubious at best because of the religious bias attributed to Christianity’s proliferation across the Pacific. Although I do acknowledge that some of what the missionaries documented regarding ancient Polynesian culture, might not have been brought to light in any other way. Still, I reference such material with caution for the simple fact that much of what the missionaries accounted for was undoubtedly subjective. I can propose however, that even if Magellan did not make contact with various Polynesian cultures, subsequent voyagers following his established route, more than likely, did.

Such European explorers would doubtless have carried full suits of armor on board their ships in case of close quarter combat with unfriendly natives, pirates or enemies of the state. In fact, when Magellan was killed in 1522 at Mactan in the Philippines, he was reported to be wearing a full suit of armor (except for his lower legs, which was how he was felled by spear, subsequently mob rushed and killed: http://libweb5.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/pacific/magellan/magellan.html).

So, if the Marquesans (and the rest of Polynesia, for that matter) witnessed armored men arriving at their shores on gigantic sailing ships, with significantly paler skin than themselves, some clad in gleaming metal skin, wielding forged weapons and speaking a completely unfamiliar language, what would this mean to them?

As late as 1779, Captain James Cook, upon his third voyage to the Hawaiian Islands, was mistaken for the god, Lono for just such reasons (and because his arrival at the end of the Makahiki, a seasonal festival celebrating harvest, centering around the god, Lono). The gods of Polynesia were considered to be ‘clear skinned’, meaning free of tattoo, as well as of pale complexion.

Could the Marquesan natives be as easily awestruck by the visage of seafaring Europeans?

It would be impossible to say for certain, although much of how early Polynesians experienced such interactions would point to a higher probability of being mystified by the alien visitors than not. Although such initial meetings were not often met with hostilities on the part of the Polynesians, the European explorers would likely have several men-at-arms standing at the ready, should things get out of hand.

What would this mean in terms of Marquesan full body tattoo not being of endemic origins but rather from evolving, in execution, from a foreign influence?

There are certainly enough potential localized causes for inspiration of creating ‘armor’ for the body, from tattoo. Turtles, both shell and skin are immortalized in much of Polynesian tattoo. Insects such as centipedes, woodlouse and walking sticks would be an obvious analog, as would certain fish and shellfish. All of these animals are frequent motifs in Polynesian tattoo. Perhaps these were not the primary inspiration behind the concept of tattoo as armor, but became the impetus once the initial grand vision had been established?

If enough time had elapsed between initial and subsequent contact, then the art (tattoo) would likely take on a life and meaning of its own. It would also make sense that after the Marquesans had figured out that these strange visitors were not in fact, gods, the superiority of having an outward layer of metal skin would be something worth emulating.

The solid black sections known as pepehipu, translates to the word ‘hammered’ and is intended to represent a pounded material such as metal or tree bark. Then there is the curious motif, kohe ta, the sword.

Much to think about considering the obvious to correlation to objects made from metal, which did not exist in early Polynesia.

At the very least, I think that what this question may prove is that as human beings, our art and what inspires us to create it can come from anywhere or anything. It also brings to light the possibility that early Polynesians did not evolve in derelict seclusion, enlightened only when the first wave of missionaries arrived to show them the true path to salvation, as many have proposed.

Perhaps the need to protect oneself from the gods did not simply stem from the potential fury of some unseen entity, but from the fact that some men were sailing on ships, masquerading as deities, which was a real and tangible threat that could not be ignored?

As I stated at the beginning of this paper, this is all conjecture. However, the closer I familiarize myself with Polynesian tattoo art, I feel that the answers to ‘why’ are not as nebulous as they once were.

Could the prospect of emulating armor, clothing or adornments be something that would even interest the Polynesian mindset?

Take Tahitian tattoo, for example.

Tahitian tattoo was universally applied to both sexes at the time of initial European contact circa 1760 (Banks 1962) but made a significant stylistic change between 1770 and the early nineteenth century. By 1830 it was stylistically degenerate and very much in decline (Gell 1993, p.123). The influence of the Europeans had such an impact on the aesthetic sensibilities of the Tahitians that their tattoo art changed to reflect this new inspiration. No longer were endemic cultural significant imagery held in high regard as much as the need to emulate the clothing of the European visitors. Striped pantaloons, argyle patterns, fleur-de-lis and other textile imagery supplanted cultural iconography and became the norm. When chief Pomare I accepted Christianity, tattooing was forbidden and not tolerated.

So, the answer then, would be, yes.

Whatever the case may be, you now know what keeps me up at night.

Peace!

After reading through your blog entry on Kohe ta. You solved one of my design problems (If it will fit).

My view, when you question the probability of Polynesian experience with metal swords and reference to the pommel over the buttocks, is the kohe ta curve is the blade over the buttocks. The ‘old style’ shows what looks like a tooth pattern on the inside of the curve. Don’t remember specifics but I have seen an Amazonian tribe that carries something that looks like a bill hook (see link- http://www.autonopedia.org.uk/appropriate_technology/Tools/Tools_and_How_to_Use_Them/Adze_Hooks_and_Sythe.html). Iron doesn’t affect the design or its use and meaning, in my opinion. They could have easily had a weapon shaped like that and lined on the inside with shark teeth. There was no need for iron experience. Although I wholeheartedly agree that iron was very prized by every Polynesian culture.

So? Am I fucked up as Hogan’s goat, or what?

Adze, Hooks and Scythe – Autonopedia

http://www.autonopedia.org.uk

The history of the adze follows very closely that of the axe. The heads were made of the same materials and the shape was

Aloha zacapuesl ,

Thank you for your input! I do encourage people to comment on my posts and offer their opinions on Polynesian tattoo.

I just want to state that I base much of my observations on the source material accumulated by Karl Von Den Steinen (and Willowdean Handy, in the post regarding Polynesian tattoo as armor). Mr. Von Den Steinen composed and published a three volume set of books in 1928 after visiting the Marquesas between 1897-98. His work is regarded as the ultimate chronicle of Polynesian culture and art ever documented. His three volumes contain over 1300 photographs and illustrations of Marquesan plastic art (sculpture and wood work) and tattoo. Every book that I have read in regard to Polynesian tattoo, references his work (albeit only a very small percentage of what is there). These books are very rare and hard to obtain. They are also very expensive, original copies are between 2-3000 dollars. I waited 6 months for my copies to arrive from Germany and paid a little less than a thousand dollars for them. They are also written in German (there is a French translation, too) and require translation.

I do not build on the work of other authors who have published books on Polynesian tattoo because I have found that much of what has been printed is simply wrong. I believe that this is because many of those authors are not Polynesian and view Polynesian art and culture from the bias of a Westernized eye. My observations come from the knowledge I have of my own culture and it is through this lens that I attempt to make my arguments. In other words, I am not ‘guessing’ so much as using what I see before me, comparing all pertinent data and extrapolating potential meaning or agency.

That being said, please allow me to address your input.

I too, felt at first, that the kohe ta could simply be an analog for a sickle or scythe type of weapon. It certainly looks like one if one imagines the curved area as the blade and the straight section as the handle. It makes sense. I even thought it could have been a variation of the Nepalese Kukri or a hand held harvesting sickle. After contemplating this for some time I concluded that the kohe ta was not a sickle or even and adze-type of weapon for several reasons:

1) The cultures that utilized the scythe or sickle were generally western, grain-crop harvesting peoples. Sickle shaped tools were better utilized as tools than as weapons and would require the use of iron to make a blade.

2) The Polynesian adze, although somewhat similar in shape, was used to make canoe hulls and its blade was a fixed piece of basalt rock. It is also known as ‘ai makamaka’ in Marquesan and ‘ko’i’ in Hawaiian.

3) In the 200 or so photographs of weapons taken by Von Den Steinen (VDS) there is no record of a bladed weapon or curved weapon for that matter except a wooden object that looks like a boomerang and was likely used a small club.

4) There is one illustrative reference to a motif called kohe tua, which Handy glossed as “back knife”. It is essentially a smaller version of the kohe ta and is placed more on the lower back and legs.

In regard to your statement that the blade could be a row of sharks teeth, there is no evidence of the use of shark teeth in Marquesan weaponry. They preferred to use bludgeoning weapons such as the u’u, or war club as well as spears and bolos. The only illustrative example of a shark tooth being utilized at all is of a small ‘surgical’ instrument with a single tooth lashed to the end of a straight handle. It looks to be the size of a small hammer.

On a side note, in regard to the niho, or tooth motif utilized in much of Polynesian tattoo, it must be said that it is only because of a somewhat modern interpretation of the triangular motif representing a shark tooth that it has become associated with that specifically. Niho are in fact teeth and do not necessarily represent a shark tooth. This motif was meant to fortify the tattoo itself by giving the tattoo ‘teeth’ so that is could be effective. Because of the fascination with Hawaiian weaponry, in particular the lei-o-mano, a spade shaped club lined with shark teeth, the assumption that all triangular shaped tattoo motifs are indeed sharks teeth are false. The Hawaiian culture utilized the shark tooth to a greater extent than other Polynesian cultures and it should be noted that specific Poly cultures used specific weapons that others did not use at all.

There are still some questions as to what a Marquesan would consider a sword and why VDS and Handy both have glossed the word ‘kohe ta’ as such. VDS glossed the break down for the word as “Bambusmesser” or bamboo knife, “Schwert” or sword and “Sabel” or saber. If the kohe ta was indeed a bamboo knife then that would account for a curved blade. The other two words, however, speak for themselves.

It is because of this fundamental lack of visual and written evidence that I based my assessment of the kohe ta in relation to the use of tattoo as armor.

I am constantly researching and updating my posts to reflect new evidence. Perhaps one day I will address the kohe ta on its own and come to a completely different conclusion? This is one reason that I found it necessary to travel to the Marquesas before completing my next book, Fundamentals of Traditional and Modern Polynesian Tattoo. There surely must exist some other illustrative or photographic evidence in the Marquesas?

Aloha!

Roland,

As always thanks for your information and education. You provide a information about a very popular but under-represented artistic and culture style. Thank you.

Zacapu.esl

🙂